How a poster was born

- katharinabiely

- Jun 17, 2022

- 43 min read

Updated: Oct 31, 2024

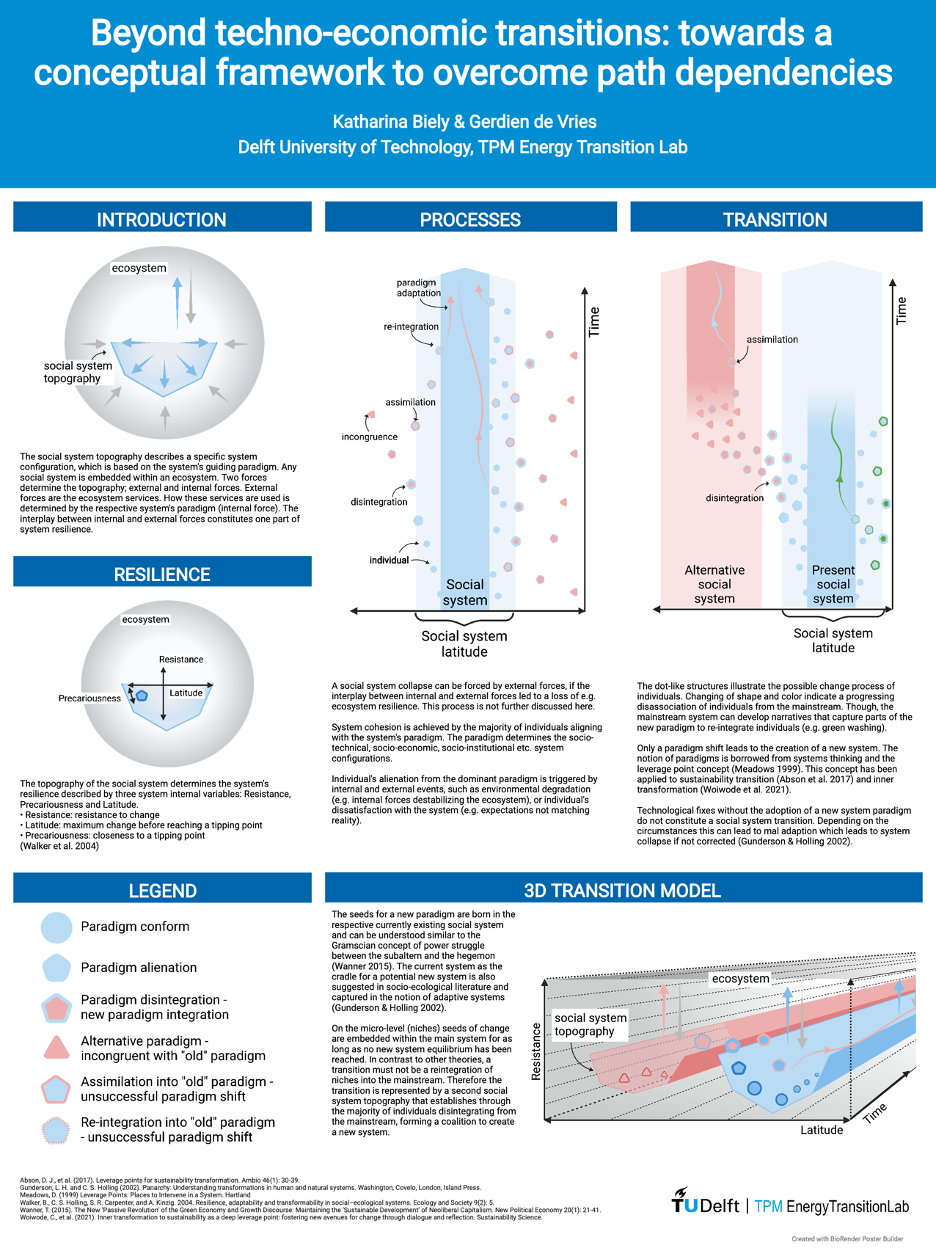

For this blog, I intend to take you on a little journey. I have developed a concept to understand transitions. The concept is not 100% complete yet and I guess it will take me some more years to complete it. In this blog, I cannot explain all aspects of the concept, because it would take too much space here. I am currently working on a paper to explain the concepts, though to be frank, I am struggling to pack the new concept in a single paper. First, there is much to explain about the concept itself, second, I need to explain why the already existing concepts and theories do not suffice. Although to me, they did not suffice, I still heavily build on concepts and theories that are already out there.

Since I build on existing theories, I am not sure if I should state that I have developed this concept. I rather blend things together in a way that seems useful to me. This is the reason I came up with it. I needed a concept that is useful to me. I think all existing concepts of transition are useful to some extent. They have been developed for a specific application and for that specific application they may very well be useful. Though, for what I intend to describe there has not been a concept that captured it. Sure, there might be one, that I am not aware of. If you are aware of such a concept let me know. So, the concept that I have developed is not necessarily a critique of other theories and concepts. It is an offer. An offer to understand transition in a certain way. This certain way might be useful for some and not so much for others.

In this blog, I want to explain the main aspects of my concept and I first want to explain how I developed it. And so, the journey begins.

Where it all began

I got a postdoctoral position at Delft University of Technology and my task is to perform research on the relationship between human behavior and the energy transition. This work is done within the TPM energy Transition Lab (ETLab). I did not have a background in behavioral science, or in energy transition. To get into the topic I started to read about the energy transition. What does it mean, and what are the themes out there? I was hoping to get enlightened about behavioral science on the way. That did not happen.

Reading about the energy transition, I continuously came across the socio-technical transition theory. Of course, I already knew this theory, but I never worked with it so intensely. However, it did not provide me with the framework I would have needed to capture the energy transition. Now you need to know that I am a proponent of strong sustainability. I am not intending to get into a discussion about sustainability here. There are many shades on the spectrum of interpreting sustainability. I am in the ecological economist corner, in the planetary boundaries corner, in the there is thermodynamics corner, in the deep transition corner. With this, I want to say that I believe that natural, social and economic values (to use the common triad describing the aspects of sustainability) are incommensurable, hence they cannot be traded off. Therefore, the environment needs to be protected, planetary boundaries need to be acknowledged and human activity needs to be in synergy with the planetary system to not degrade the natural capital (which cannot simply be repaired with financial or human capital).

Our current societal system does not follow strong sustainability but weak sustainability. That is the environmental and resource economics corner, the human ingenuity can defeat the laws of physics corner, the damages caused by overstepping boundaries can be repaired corner, the if one recourse is depleted we just substitute it corner, the some superficial adaptations suffice corner, the technology and market-based mechanisms solve it all corner. Weak sustainability suggests the commensurability of values, which allows to trade off environmental damage with financial and/or human capital. Thus, as long as the economy grows the damage done to the environment can be repaired somewhere down the road.

I am a bit polemic here. As stated, there are many shades in between these two. Though, we are far from strong sustainability, which is where we need to get to halt climate change at a bearable level and stop environmental destruction in so many areas. We also need strong sustainability to end injustice, poverty, and the exploitation of humans. To make this change happen, we cannot simply put a new product on the market. We need to change our whole social system and with this our economic system.

The energy transition needs to be embedded in a sustainability transition. It needs to be embedded in a transition towards strong sustainability. Thus, it is not only about buying an electric car, getting your house insulated, or putting a solar panel on your roof. It is not only about making people buy greener products and making people accept some technology. It is about doing all of the above within a new social system that is based on a paradigm that respects nature and human beings.

However, getting back to socio-technical transition theory, this theory does not capture such a transition. I want to emphasize; that the theory is great to understand the mainstreaming of technology. Though, this is not what I am interested in. Below you see the illustration (Figure 1) of the socio-technical transition process. I have taken this one from Vandeventer, Cattaneo et al. (2019), but you find it in literally hundreds of scientific publications. I added some red squares to highlight some of the text I am struggling with.

Before expanding on the text, the image itself does not provide a transition in my eyes. There are some lines, the regime, that get a bit disrupted, but then they continue. After some turbulence, the flight continued as planned. It is a linear process with some irregularity in the middle. To me, a transition is something different. The text does neither talk about a transition, but rather about something being integrated into something existing. In the middle red rectangle, it says: “Elements become aligned and stabilize in a dominant design.” The upper red square text states: “Adjustments occur in socio-technical regime.” Maye it is just about terminology, but an adjustment is not a transition or transformation. And an alignment does neither sound much like a transition.

The lowest red rectangle talks about visions and expectations. One needs to read the explanation to understand this. Because the question is who’s visions and expectations. Following the explanation of Grin, Rotmans et al. (2010) even if the visions in the niche are different from the vision of the regime, some form of alignment of the niche vision with the regime vision needs to happen to allow the niche innovation being integrated into the regime. Thus, any out-of-the-box thinking becomes watered down in the transition process, as the innovation is integrated into the regime.

So socio-technical transition theory did not provide me with the frame I would need to describe the transition I envision. From this, a quest began to come up with an alternative.

Figure 1: Socio-technical transition theory

Finding an alternative

I cannot exactly reconstruct the process. Though I was reading different papers about transition. When I started working on this, I used my tablet a lot and worked in the app LiquidText. There I had different folders, one of which contained transition literature. I had other folders about path dependency, resilience, paradigms, ethics, economics, or behavior. So, the ideas that came up were cross-fertilized by papers from other folders. And of course, the papers in these folders are related. It could be argued that resilience and path dependency are two sides of a coin and that both are related to transition theory. To give you an impression of what I have been reading I am listing the documents in the transition folder:

Scientific literature:

Grin, J., et al. (2011). "On and agency in transition dynamics: Some key insights from the KSI programme." Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 1(1): 76-81.

Alexander, H., et al. (2017). "Building a middle-range theory of Transformative Social Innovation; theoretical pitfalls and methodological responses." European Public & Social Innovation Review 2(1).

Pel, B., et al. (2020). "Towards a theory of transformative social innovation: A relational framework and 12 propositions." Research Policy 49(8): 104080.

Sovacool, B. K. and F. W. Geels (2016). "Further reflections on the temporality of energy transitions: A response to critics." Energy Research & Social Science 22: 232-237.

Turnheim, B. and F. W. Geels (2012). "Regime destabilisation as the flipside of energy transitions: Lessons from the history of the British coal industry (1913–1997)." Energy Policy 50: 35-49.

Fouquet, R. (2016). "Historical energy transitions: Speed, prices and system transformation." Energy Research & Social Science 22: 7-12.

Kern, F. and K. S. Rogge (2016). "The pace of governed energy transitions: Agency, international dynamics and the global Paris agreement accelerating decarbonisation processes?" Energy Research & Social Science 22: 13-17.

Hopwood, B., et al. (2005). "Sustainable development: mapping different approaches." Sustainable Development 13(1): 38-52.

Markard, J., et al. (2012). "Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects." Research Policy 41(6): 955-967.

Speth, J. G. (1992). "The Transition to a Sustainable Society." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 89(3): 870-872.

Loorbach, D., et al. (2017). "Sustainability Transitions Research: Transforming Science and Practice for Societal Change." Annual Review of Environment and Resources 42(1): 599-626.

Köhler, J., et al. (2019). "An agenda for sustainability transitions research: State of the art and future directions." Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 31: 1-32.

Geels, F. W. and J. Schot (2007). "Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways." Research Policy 36(3): 399-417.

Vandeventer, J. S., et al. (2019). "A Degrowth Transition: Pathways for the Degrowth Niche to Replace the Capitalist-Growth Regime." Ecological Economics 156: 272-286.

Im, H. B. (1991). "Hegemony and counter-hegemony in Gramsci." Asian Perspective 15(1): 123-156.

Reports:

World Economic Forum (2020). Dashboard for a New Economy: Towards a New Compass for the Post-COVID Recovery.

World Economic Forum (2020). Markets of Tomorrow: Pathways to a New Economy.

World Economic Forum (2020). Vision Towards a Responsible Future of Consumption: Collaborative action framework for consumer industries.

Forum for the Future (2020). From system shock to system change – time to transform. The Future of Sustainability.

World Economic Forum (2019). Fostering Effective Energy Transition.

World Economic Forum (2020). Fostering Effective Energy Transition.

LiquidText is a fun app. I used it because of the home office situation, and I needed something to scribble on papers, without printing them. The app allows just that. It also provides a workspace next to the papers on which one can write and scribble. I fully made use of this possibility and thus, the first sketches of the transition process were made in the app.

Figure 2:LiquidText workspace showing the first sketches of the transition concept

Figure 2 gives you an impression of the app and it shows the first sketch. I thought of some sort of disruption happening, most likely caused by a crisis, which could lead to the establishment of a new trajectory. I already distinguished between a trajectory that bounces back (resilience) and the possibility of an alternative that is completely different from the current trajectory. Note that I also already had the idea of some sort of unwanted resilience, in case the trajectory is unsustainable. You can also see that the dashed line has two colors. The pink line is the exact continuation of the past trajectory. The green addition is the uptake of alternative ideas to support the bounce back. These initial ideas are also present in the latest version of my transition concept, though the graphics have improved.

Figure 3: LiquidText workspace showing the first sketches of the transition concept

Figure 3 shows the further development of the previous idea of the transition process. The larger sketch with the dates (2008, 2021) shows the process along a specific timeline. For the rest, it has stayed the same. The crisis of 2008 is connected with a bounce-back related to the increasing support of the green economy and green growth. The 2021 crisis is similar in terms of narrative, as we find again the notion of building back better, where the back is understood to be greener and more inclusive. That we are talking about building back better is indicative of there being no intention of a transition, since the intention is to go back. Within the app, I made a connection to the report by the Forum for the Future (2020) and the quote: “So the question now is: are we on the verge of a breaking point – or can we use this shock as a tipping point for change?” In the purple box, some of my thoughts about the transition are captured. First, I describe the sketch, then I discuss the implications for the individual level.

My thoughts:

“I would say that on an individual level people are having a crisis as they are unhappy with the current trajectory. Some of them adapt, some to a greater, some to a lesser degree. A parallel society is created. But the parallel society accommodates with the current trajectory […]. To respond to these people, the market system provides products that better fit the demands of these alternative people. Through this process, which is also a sign of resilience, the rift between the parallel society and the mainstream trajectory diminishes.

I would however argue that the crisis will increase and people’s discontent with the mainstream will increase. If a deep crisis comes along (potentially multiple crisis), the resilience of the mainstream trajectory will be overpowered. Then, a new trajectory will follow.

What is the new trajectory? Seeds to the new trajectory have been sown earlier. How this will look like, will then depend on many factors. There will be power struggles, there will be those who want to maintain their power and wealth, there will be those who want to gain in power, there will be those who want to overcome all of this. I suppose that in case of a deep crisis the transition will be chaotic and harmful.”

The smaller sketch in Figure 3, captures the market mechanism. It is again connected to a publication (World Economic Forum 2020), which discusses how markets respond to challenges. They apply a socio-technical transition lens to explain the transformation of markets (see section 3.3. in that publication). For the selection of new markets, it is stated: “New markets are meant to address the key challenges that society faces today.” I connected this to other quotes from a World Economic Forum (WEF) report:

“In the light of these trends, and the potential for the consumer industries to be an instrumental force in the world’s pandemic recovery, the World Economic Forum and its partners in the Consumer industries have come together with business leaders from […]. The community has since shifted its focus towards realizing broad, transformative change. […] Ultimately, the game changer will be individual and collective ecosystem actions working in concert. Only this way can the world develop and adopt practices that will result in an equitable, resilient future. Only in this way can wide-ranging responsibility and sustainability become an integral part of growth, with no exceptions” (World Economic Forum 2020, p. 11f.).

The ecosystem is not meant in a biological sense but as a complex of synergistic business activities and actors. Aligning the (business) ecosystem with common goals should then “accelerate inclusive growth.” The World Economic Forum explains that: “ We are first and foremost human-centric, creating shared values and operating with integrity to ensure a sustainable and resilient future.” They highlight that they want to “advance responsible consumption for the benefit of businesses and society” and they want to use the collaborations with the Consumer Industries to build on the WEF’s Great Reset to “improve the foundations of our economic and social system” (World Economic Forum 2020, p. 5). The lingo of the Great Reset does, I think, not convey the notion of a transition. Resetting my computer has so far never led to a transition (or transformation) of it. But maybe I am doing something wrong, and I have to call Shia LaBeouf.

The WEF is a leading institution in shaping the future of business (and political) interests and thus, their understanding of a transition should not be neglected. They describe a transition in terms of socio-technical transition, where a niche development picks up new trends, such as green products. These niche developments are then reintegrated into the existing system, which is based on the economic growth paradigm. The ability to pick up on trends and integrate (assimilate) them, is one reason why the current economic system is resilient (below, I will explain using the concepts I have developed). The ability to appropriate sustainability is exemplifying this. Sustainability became weak sustainability. Out of a green economy, green growth was born; out of an inclusive economy, inclusive growth was born.

I think that the ability to reframe alternative (potentially threatening) narratives to make them blend into the growth narrative is key to understanding why a transition has so far not been observed. The other day I have commented on a post from the European Environmental Agency showing a video about the doughnut economy. The video was clear about the need to change our economic system, but it abstained from stating that the growth paradigm needs to be abandoned. The latest IPCC reports are, as Timothée Parrique enthusiastically highlights in his Twitter feed, rather clear on the damage our economic system is causing. On Twitter, I commented on his enthusiasm saying that there is still no clear statement from the IPCC to abandon the growth paradigm. In a webinar hosted by IPCC report authors, I asked via the chat function why the IPCC is not clearer on the growth debate. The question was watered down, and the respondents talked about metrics (GDP) and the need for a new metric (which there are alternatives for quite a long time now, but they are not employed). One respondent stated in the chat that clear statements about the need to abandon the growth paradigm would not get the summary for policy makers approval.

It is increasingly acknowledged that we need a system change and a paradigm change. Though, this is also all too often appropriated to fit the current growth paradigm. Let me show you:

“The bottom line is that, while the pandemic has hurt us all in one way or another, it has grossly worsened conditions for people who were already poor, marginalized or unprotected. It has brought their issues into stark relief. It has shown the interconnectedness of their plight, the health of economies the world over and the health of the planet. It has shown how important it is to address the challenges the world faced before “COVID-19” was part of the general vocabulary. If the global economy rebounds to pre-pandemic spending levels, without undergoing game-changing transformation in the process, the recovery will be false and short-lived.

That’s why, even as the consumer industries continue to triage the immediate crises their businesses and communities face, they must also address the underlying systemic challenges that have so exacerbated the pandemic’s effects. These include poor nutrition and lack of information and resources to enable better diets and healthier lifestyles; pollution and climate change; inequity and inequality; and eroded levels of consumer trust in business.

The reality, however, is that these are systemic problems and they require systemic solutions. No single company or industry can effect transformative change at the scale needed to solve these issues. It will take the actions of individual businesses and a concerted, collective, ecosystem-level effort, involving engagement from business, government, social and academic leaders – and consumers themselves“ (World Economic Forum 2020, p. 8).

While this all sounds nice, it is the same WEF report that propagates continuous economic growth as one of their tables exemplifies.

Figure 4: Vision and goals of the WEF (World Economic Forum 2020, p.12)

In all these years of dealing with sustainability issues and the transition towards sustainability it has been crystal clear; you can change whatever you want, but don’t touch the holy grail (the growth paradigm). The socio-technical transition theory accommodates this. It accommodates the current paradigm and still offers a narrative on how transitions can happen. It supports the trust in human ingenuity, who first of all came up with the market mechanism and second continuously provides new technology to be marketed via this market mechanism.

Figure 5: LiquidText workspace showing the first sketches of the transition concept

This messy sketch (Figure 5) is about the idea of systems being able to operate within a certain bandwidth. I am still using this bandwidth concept, but I changed terminology, as I figured that the idea behind it is used in resilience theory. The purple text next to it is once more explaining my beautiful sketch.

My thoughts:

“This illustration is another layer of this concept. I assume that for each subsystem, there is an upper and lower bound/threshold. Above and below this threshold the system does not operate in the long run. It can operate in between, though there is an optimal area within this bandwidth. The closer to the edges the system operates, the more stress is created. If too much stress is created the system collapses.

Certain factors within the system can adapt, but there are factors that are fixed. Also, the adaptions are time restricted. E.g., Adaption in biology is bound to a fixed time horizon.

It needs also to be noted, that the environmental system does follow natural laws that cannot be altered. The economic system is a human invention and can thus be changed entirely. Social organization cannot change entirely, as there are parts of human nature, which are hard or impossible to alter. E.g., the need for interaction.

This is related to the previous graph, as this one shows that the constructed economic system operates in a bandwidth that constantly overstretches the social and economic system boundaries. The result is crisis. So an economic system would need to be created that does lay within the bandwidth of the other subsystems.

I think that is connected to the doughnut economy.... get that book and reared it [still haven’t].

For a new system what is the optimal bandwidth? Can this be characterized?

Thinking about the change:

So as the subsystems are running incoherent problems and crisis are the result. The magnitude of the problem and the crisis are an indicator for the incoherence of the subsystems.

I am wondering on an individual level if psychological illnesses are an indicator of people constantly living at the upper or lower bound. Chronic stress means that people are not living in their comfort zone. Sure, some amount of stress is good. But it should not be a constant. If stress levels are constantly high, there must be something wrong structurally. E.g., the economic system being created in a way that it is not in coherence or in synch with the human bandwidth.

Listening to the Ted talk of Kate about the Doughnut Econ, I think the difference is that I think that there is an upper and lower bound to each subsystem. It is not that the Ecosystem alone gives us an upper limit, I think that humans and human societies have an upper bound as well. Think, that humans cannot be without interaction, but humans can also have too much interaction. So, there is an upper and a lower bound.”

Welcome to my head… I hope you enjoy the ride so far.

To let my supervisors, know what I am working on I presented these ideas. To this end, I tried to provide some nicer sketches. On the 16th of February 2021, I presented the sketches, which were still of low quality (Figure 6).

Figure 6: beautiful sketch of the transition process

On the 26th of March 2021, I presented these ideas at a TU Delft internal group. At this time the sketch was a bit better (Figure 7), and I had started to develop a causal loop diagram capturing these ideas. I will not add the causal loop diagrams in this post as it would lead too far. At the systems dynamics conference 2021, I had the chance to present the causal loop diagrams. I got good feedback on them. I planned to translate them into a stock and flow model, which I haven’t done to this point.

Figure 7: even more beautiful sketch of the transition process

Figure 7 combines the ideas captured in the previous sketches. You can still see the timeline, the trajectory, the disruption, the notion of unfortunate resilience, and the alternative trajectory indicating a transition. However, I added the bandwidth idea (thicker stripes) and the consumers (dots). Similar to the socio-technical transition, I have mostly thought about a transition facilitated (or blocked) by the market. I focused on the economy as a system, instead of on the social system as a whole. I suggest a difference to socio-technical transition, is that I took the consumer perspective instead of the inventor perspective. That was because I was focusing on the role of individuals in the energy transition. Thus, the question was, why should people want to be part of an energy transition?

I think that people are dissatisfied with what the market offers in terms of sustainable products. People who are dissatisfied might have a different mindset, as they ask for products that others (the majority) do not. These individuals either become inventors themselves, or entrepreneurs pick up on these trends (as described by WEF) and provide the products. If that happens dissatisfied people are reintegrated into the system. Of course, another difference between my concept and socio-technical transition is that I do provide the option of an alternative trajectory, which to me describes an actual transition.

I further developed the ideas, while working on other projects along the way. By May 2021 I coded the illustration in R to make it look a bit nicer (Figure 8). Around this time, I submitted the idea to conferences. I was accepted at most of the conferences, though I did not go to all of them. An abstract does not tell much but being accepted at conferences gave me the confidence that what I am working on is interesting.

Figure 8: sketch of the transition process coded in R

Mid-May I suggested to submit the concept to a special issue, which would focus on an outlook for the next 10 years in transition research. I was a bit hesitant to submit it to that special issue, because it was only allowed to use 1000 words. I knew that with that limited amount of space I would not be able to explain it all. On the other hand, I thought it would be a nice opportunity. Long story short, it got rejected. The editor argued:

“Your contribution did not convince us that transitions research is about adaptation rather than transformation. The level of your critique is targeted at a very high-level of the transition studies field in general rather than any particular approaches or concepts, which makes it difficult to see the concrete implications. You also simplify transitions by leaving out structural changes on production and consumer sides. So transitions are not only about technical innovations – which is well recognized in the literature. The paper also lacks a definition of what is precisely meant by adaptation. The term is problematic anyway because already used w.r.t. climate change (in turn related to a low-carbon transition) with a particular meaning different from that here. Invoking the use of “resilience” adds more terminology without adding much to understanding.“

The feedback from the editor resonated with the fear I would not be able to explain all the concepts in a 1000-word paper. I knew from the beginning that if I come up with something new that argues for transcending the socio-technical lens to describe a sustainability transition, I would have a hard time getting it published. It needed to be good, very good, to get out there. Since you cannot yet find (maybe you never will) a scientific paper out there describing my concept, you can conclude that I have not yet managed to publish it. Though, after the special issue attempt, I have not tried again. That was in part because I knew I had to further develop it and in part because I had no time to do so.

Before expanding on some conceptual challenges, let me expand on some TPM ETLab internal discussions related to the special issue submission.

Discussing the special issue submission

After writing the paper, the TPM ETLab members read it and gave me feedback. In a presentation held on the 1st of June 2021, I addressed some of the raised points. My presentation had the title adaptation is not transition. The first slide was a hidden slide, but it showed an example from biology: the adaptation of Darwin’s finches and the transformation of a caterpillar into a butterfly.

To explain the difference between transition and adaptation I referred to literature. Walker, Holling et al. (2004) defined transformability as “the capacity to create a fundamentally new system when ecological, economic, or social […] conditions make the existing system untenable.” Adaptability is described by Folke, Carpenter et al. (2010) as part of resilience. “It represents the capacity to adjust responses to changing external drivers and internal processes and thereby allow for development along the current trajectory (stability domain)” (ibid.).

In the paper, I wrote: Adaptability is a function of resilience. The main difference between adaption and transformation is that the former allows the system to remain within the current trajectory while the latter refers to a change of this trajectory (Folke, Carpenter et al. 2010).

In the internal discussion, it seemed that the differentiation between adaption and transition that I referred to in the paper evoked confusion. Though I have to admit, I could not really reduce this confusion. All I could do is referring to the literature which expands on the terminology. As shown above, the editor of the special issue had a similar comment. In the special issue manuscript, I did not include the socio-technical transition figure with the red squares highlighting the terminology used in socio-technical transition literature. However, in this presentation discussing the manuscript I did. I think to a certain degree this led to some clarity. Though, as you will see in a bit the problem of framing something as a transition and or an adaptation might lie somewhere else. However, it is noteworthy that understanding the difference between transition and adaptation made me read socio-ecological papers, which expand on these terms. I could not find such clear elaborations in socio-technical transition theory publications (but there are many and I may have overlooked it).

Another sentence in my manuscript that evoked skepticism was: “While this [the socio-technical transition theory] concept has its value to describe technological change it does not describe a transformative process of the overall socio-economic, socio-institutional or socio-ecological system. It describes a niche innovation being integrated into an unsustainable system. Hence, it describes an adaptation process of the current socio-economic system.“

The feedback to this passage was that others might object to this claim since others may perceive a technological change as something deeply disruptive. I had several opportunities to test this, and I can state, that the feedback is indeed validated by the tests. This is connected to the issue of framing something as adaptation or transformation. I have never challenged the fact that the introduction of cars or the internet has been disruptive. Though, when I talk about system change, I talk about a change of the paradigm that organizes our social system. This paradigm, economic growth, has not been altered by any innovation so far. The car has not led to humans being less interested in consuming stuff we do not need. The invention of the car has not led to humans abstaining from driving cars because doing so harms the environment, which in the end, harms us. The internet has neither. Rather it had the opposite effect. It is much easier to consume. I am not challenging that the introduction of cars changed infrastructures, legislations, certain social structures, etc. But none of these changes touched on a paradigm change.

Do some technologies have the potential to facilitate such a paradigm change? Yes, I think so. The internet permits means of communication that have not been there before. The spread of certain information may very well lead to a paradigm shift.

Figure 9 slide from a presentation showing the idea of a trojan horse, inspired by Gramsci

This potential led me to think about the notion of a Trojan horse and it reminded me of Gramsci (Figure 9). I think that this would in fact be an interesting research avenue. How can the system be transformed from within? I have not found an answer to this, though, I have not expanded on this idea. It would be along the lines of a technology that most people have access to and how this technology could lead to a paradigm shift that would make people abandon the growth paradigm. During my master’s when I learned about Gramsci’s writings, it was presented as he suggesting change coming through social interaction at informal gatherings. People sitting together with a glass of wine discussing ideas. Revolutions born in the pub, so to say. That might still be an option, only that the means to proliferate radical ideas have changed (internet). Anyway, I did not expand on that idea any further. If you do, let me know, I am happy to learn about it.

To continue with paradigm changes, we have to look at values. One paragraph in the manuscript stated: “Technologies do not transform the rationale our economic system has been built on; neither do they transform our core values (Baum and Gross 2017).“ On this segment, I got the feedback that this might not be true. The internet was provided as an example. As stated above, I doubt that the internet itself provided a value change. The internet can influence value changes through its ability to provide or block information. Technologies might evoke discussion about values a society agreed on. Like genetically modified organisms, or the use of nuclear energy. The discourse provided alongside the introduction of the technology might lead to some value change. We may discuss values such as safety, or privacy. Though, I am not aware of a technology that has challenged the growth paradigm. Well, that is not correct. Open-source technology (sharing economy) could be an example. Still, I have not seen it to be successful in overthrowing the econ growth paradigm. At times the sharing economy or the service economy are described as systems that would allow the economy to grow but decoupled from resource consumption. Thus, there as well the attempt is to appropriate alternative ideas to fit the paradigm in place. As mentioned above, this process of appropriation is nicely illustrated by socio-technical transition theory.

I may add here, that since values and worldviews are essential to understand where I am coming from, if one does not agree with my strong sustainably stance, all my arguments can easily be brushed away. When a weak sustainability stance is used, we do not need to change our paradigm. When a weak sustainability stance is applied an adaptation equals a transition.

In my manuscript, I argue that for a transition the paradigm needs to change, which is discussed by Meadows (1999). Accordingly, I wrote in my manuscript: “Meadows (1999) has prominently outlined a hierarchy of potential intervention points. If something is inherently wrong with the goal of the system only the replacement of the goal will solve the problem (Abson, Fischer et al. 2017).” The feedback to this segment was that the Multi-Level-Perspective would also argue for a regime change. Thus, the call for a paradigm change might not be new.

I did not have the best reply to this feedback at the time, but I have a better one now (I believe). A regime change is not a paradigm change. Though, the socio-technical transition theory literature describes that values are on the regime level and that these values lead to a specific configuration of the regime. Though, values are not really addressed in socio-technical transition theory. Which is why some authors tried to add them. Göpel (2016) has added a meta-level to give paradigms a specific location within socio-technical transition theory. Naberhaus, Ashford et al. (2011) argue that the paradigm is on the landscape level and that the landscape needs to change. With this Naberhaus, Ashford et al. (2011) may contradict socio-technical transition theory. Though, it has to be stated that researchers using socio-technical transition theory are not really clear on what to find on which level (Grin, Rotmans et al. 2010, p. 135). Anyhow, Williams, Kennedy et al. (2017) concluded that within the transition management literature (reviewing socio-technical transition literature) a paradigm change is not considered.

Thus, yes, something changes on regime level in socio-technical transition theory, but the paradigm is not addressed. This made me rather confused about the work of Vandeventer, Cattaneo et al. (2019), who apply socio-technical transition theory to explain how degrowth could get its breakthrough. I found socio-technical transition theory to be ill-fitted to explain the breakthrough of degrowth, which for sure will require a paradigm shift.

The presentation ended with a quick insight into parallels between theories that I was thinking about. I was wondering how far the notion of Panarchy relates to the multi-level-perspective. I further quickly showed the similarities and differences between my idea and the socio-technical transition theory.

Conceptual challenges

Apart from explaining my transition concept linguistically, I also tried to illustrate it visually. That brought its own challenges. The comparison with the socio-technical transition theory potentially added to the challenge. Why is the new system below and not above? Or could it even be on the same level, but change qualitatively? How should the transition path look like? Which colors to use? Should I use colors after all? What are the axes, should there be axes? What are the levels? What terms and labels to use within the illustration?

To get some answers I went on a little excursion to explore these questions. I developed illustrations that captured different qualities (Figure 10). Certain qualities, such as the labels and the axes were always the same as I was at that moment mostly interested in the arrangement of the transition path, the colors, the use of different structures, etc. I have to state that I did not do an in-depth study. Though, it was enough to provide me with some insights. I distributed this to a limited amount of people within the University as well as to certain Facebook groups dealing with transition topics. I learned that the label of the y axis was not good and that colors are preferred. For the rest, there was no real agreement or trend. However, I found that some perceive the new system being lower than the old one as a bad thing, while others perceived the same arrangement as good. This is as some connect the system being lower to less emission (despite I did not indicate that this would be related to the energy transition). Others perceive lower as worse off.

In essence, I found out that no matter how I depict it, there will be unintended connotations. There will be people who like it, and others who won’t. In any case, I would have to invest quite some time to come up with an illustration that is as clear as possible and that is not too much connected with existing concepts as it may lead to misunderstandings.

Figure 10 examples of how a transition process could be depicted

After this excursion, I organized a workshop within the TPM ETLab to work on the different understandings of the terms adaptation, transition, and transformation among the lab members. I have written about this elsewhere. Shortly after that workshop, my engagement with finding an alternative transition concept stopped. I was working on other projects and at some point, wanting to understand the individual aspect better, I decided to read more about behavioral science. The result was a working paper, which you can find online. I have written about this working paper in another blog.

The working paper was a good exercise and although not intended it added much to my understanding of transitions. As Sovacool and Hess (2017) have pointed out a lot of transition research is related to behavioral science. While writing this working paper I again came across the socio-technical transition theory. A little teaser: in the working paper you also find a visual connection between socio-technical and socio-ecological thought. I will not expand on what I learned while writing this working paper since this blog is already too long for a blog. Still, mentioning this may help you to understand that I approached this issue from different angles, with breaks in between, with time to digest and think.

After the working paper was done, the 3rd International Conference on Energy Research & Social Science (ERSS) was on my agenda. I had submitted to the conference in 2021 but due to the pandemic, it was postponed to 2022. My abstract got accepted as a poster. I am not a fan of making posters. I think in the research field I am in they are less prestigious. Though, I do not care about this. Rather my reason for not being enthusiastic to make a poster is that it is much harder than a presentation. You need good visual illustrations of your story, and you need to present your idea on just one page. When I got notified that the abstract was accepted, I was not sure if I even wanted to go to the conference, because at that point I did not have further developed my ideas. All I had was some crappy sketches. Though, in the end, I thought, in the worst case it is going to be a crappy poster. So, I started working on it.

The transition concept

Here we are, the journey is almost over. Well, I have to write much more about the concept than I can in this blog. I will only superficially explain all the illustrations that can be found on the conference poster. Plus, as an addition, two more illustrations are added and explained here.

To illustrate the process, I was once more first scribbling some sketches on a piece of paper. That gave me a rough idea of what I wanted the transition process to look like. My main problem then was to find a program in which I could implement it. I do a fair amount of illustrations in PowerPoint, but the illustrations I wanted to do, could not be done in that program. I started a search and by accident, I came across BioRender, which I could access with my TU Delft credentials. It is a program specifically for making nice illustrations in the field of biology. They have all kinds of icons available (from cells to mushrooms). The icons were not of help to me. Nevertheless, the program offers some simple tools that allowed me to implement my ideas.

In the end, the illustrations of the concept were developed relatively fast. Though, as you have seen, I had this in my head for quite some time. After the main elements of the illustrations were developed, I changed some of the positionings (from horizontal to vertical – thanks to my little sister!) and I changed the labeling a lot. I have no title for my transition concept… My little baby is nameless…

So here I introduce the nameless creation.

The concept that I will present is inspired by socio-ecology especially by the book Panarchy (Gunderson and Holling 2002), and the concept of resilience (Walker, Holling et al. 2004), by systems thinking and leverage points (Meadows 1999, Abson, Fischer et al. 2017, Woiwode, Schäpke et al. 2021), by my research on behavioral science (Biely 2022), by political economy, especially by Gramsci (for example Im 1991)), and of course by socio-technical transition theory.

Figure 11: 3D-transition model

Figure 11 illustrates the 3D transition model. More illustrations will explain specific aspects of this figure. For example, the meaning of social system topography, as well as the axes (resistance and latitude), will be explained below. The 3D transition model illustrates that alternative social systems are on the same level parallel to each other. This overcomes the above/below, good/bad connotation, I have referred to before. On purpose, I did not choose the color green for the alternative social system, since I want this model to be applicable to any social system transition. Some may think about political parties when looking at these colors, but the colors have nothing to do with any specific political party. Neither is the position of the social system along the latitude axis related to a political orientation. As will be shown in another illustration, infinite potential social system topographies could be added along the latitude axis. The reddish social system topography is transparent in the beginning, to illustrate that it only exists as potential.

In contrast to socio-technical transition theory, this model understands systems being embedded in other systems (socio-technical transition theory does also use a systems perspective, though, I would argue the perspective applied is limited. I cannot expand on this here). Accordingly, the social system is embedded within the ecosystem. I had different names here. Another idea was to call it substrate, but I found this too abstract. Or one could talk about systems and subsystems, but many will be troubled by this as well. Of course, others will be troubled because of the term ecosystem. I decided against landscape, because I did not want to induce the connotation of a topography there. That is although, for sure the ecosystem has a topographic character as well (Steffen, Rockström et al. 2018). I suppose that is the merit of a systems perspective where characters of one system apply to the other systems as well. Though, depending on the focus of analysis one may display a specific character only on the subsystem level, for example.

For the purpose of this concept, the topography of the social system is more important. Consciously I went for the term social system, instead of socio-technical, socio-economic, socio-institutional, etc. This choice is related to the differentiation between natural and social systems within the book Panarchy (Gunderson and Holling 2002). Indeed, the interaction between the ecosystem and the social system would be described as the socio-ecological system.

Figure 12: social system topography, left (a) explains the interplay between internal and external forces, right (b) explains internal factors determining resilience.

Figure 12a, provides more explanations about the social system topography. The idea of using a 3D object instead of a flat object is related to the notion of resilience within socio-ecology (see Figure 12b). As a side note, I wanted to use a 3D model early on, but I had no idea how to implement it. Only after I simplified the initial illustration, after I had distanced myself from it, I could sketch a 3D version. And of course, I needed the right program to implement the sketch!

The topography of the social system is created through internal (social) as well as external forces (ecological). Actors that make up the social system follow a certain paradigm. Based on that paradigm forces are employed to create a specific social system topography. The mobility system, the energy system, the economic system, the political system, the economic system, the institutional systems, etc. are all embedded within the social system, and all together create a system specific topography. Think of a fingerprint unique to a certain paradigm.

Of course, since the social system relies on natural resources, the shape of the topography is also depended on the resource availability, as well as, on the exchange between the social and the ecosystem. The internal forces can react to external forces to change the topography slightly. However, as I will show later (see figure 14), such changes can lead to frictions within the social system (this is described in socio-technical as well as in socio-ecological literature). Only slight changes are possible because the topography needs to be in line with the respective paradigm. A dramatic change of the topography would indicate a paradigm shift. Thus, a paradigm has a specific social system topography that determines specific configurations of subsystems (such as the socio-technical system) within that social system as well as the exchange between social and ecosystem.

There are similarities between this topography idea and the notion of regime within socio-technical transition theory. Grin, Rotmans et al. (2010) describe that the regime is determined by the actors’ subjective preferences. Thus, it can be argued that the mental space of actors is of similar importance in both concepts. Furthermore, the patches (culture, policies, industry, markets, etc.) within the regime describe different parts of the regime, which provide specific characteristics to that regime. In both cases are the subsystems (or patches in socio-technical terms) part of the system (which I call social system, and socio-technical thinking calls it socio-technical regime). However, in my concept, the mental space has more explicit relevance for a system transition. Furthermore, as I will describe below the topography helps to understand resilience (or lock-ins).

The relevance of the paradigm to give shape to the system is borrowed from systems thinking and the concept of leverage points. Meadows (1999) identified 12 leverage points that are ordered in a hierarchical manner. The lower leverage points describe the system’s goal and paradigm, the higher leverage points refer to parameters, stocks, and flows of that system. Higher leverage points are easier to change, but have less potential for changing the whole system. The reverse is true for lower leverage points. The relevance of tackling these lower leverage points for transition has been discussed by others as well. Abson, Fischer et al. (2017) has applied it to sustainability transition, Woiwode, Schäpke et al. (2021) to a mental transition. The same understanding of leverage points is applied to this concept. To achieve a system transformation the paradigm needs to change. This paradigm change will lead to a complete change of the system’s topography.

Figure 12 b explains the system’s internal variables determining the system’s resilience. One force is an external force, or rather it is given by the interaction between system and subsystem. This aspect of resilience is described by the concept of Panarchy (Gunderson and Holling 2002, Walker, Holling et al. 2004). Systems (ecosystem) and subsystems (social system) are connected and influence each other. Shocks within the ecosystem are transmitted to the social system. This is also very well described by Grin, Rotmans et al. (2010, see e.g. p. 15, 56ff.) as well as Geels and Schot (2007) framed as different types of landscape shocks. Though, the social system can also negatively impact the dynamic stability of the ecosystem. If such shocks to the ecosystem lead to a drastic change of the ecosystem (i.e. shifting to another dynamic equilibrium state such as from forest to grass-land) it impacts the social system in turn again. Thus, there is a feedback between the ecosystem and the social system. Whether that change in the ecosystem equilibrium state has negative impacts on the social system or not depends on the change. This is described in chapter four in Panarchy (Gunderson and Holling 2002). A prominent example within human history of a negative backlash is the easter islands. Though, this is not the only example. Chew (2001) describes that human history is full of such examples. Climate change and the general degradation of the environment that human societies are causing now are just another addition to this sad history of environmental overexploitation by humans.

Thus, the paradigm together with the external forces shape the social system topography. Though, this topography can impact the dynamic stability of the ecosystem in a way that the ecosystem shifts to another dynamic equilibrium. This shift can have negative impacts on the social system (e.g., climate change). The only way to substantially change the negative impact of the social system on the ecosystem is to change the topography, and hence the paradigm of the social system.

The internal variables determining the system’s resilience are latitude, resistance and precariousness. These variables make a topographical illustration of the system necessary. One can think of resilience as a valley and a ball within this valley, where the ball indicates how close the system is to being pushed into another dynamic equilibrium state (another valley). According to Walker, Holling et al. (2004), the latitude describes maximum changes the system can handle before losing it stability to bounce back. Resistance is captured by the depth of the valley and refers to how big shocks need to be to push the system close to the threshold. Precariousness describes how close the system is to the threshold.

To avoid confusion, it needs to be mentioned that the point-like elements in the Figures 11, 13, and 14 are referring to individual actors rather than to the overall state of the system in relation to the ecosystem. Though, it can be translated that the precariousness is determined by where the majority of actors are located within the social system topography. In Figures 13 and 14 (below), the topography has two different shades. This is to indicate the precariousness aspect, where the lighter shade indicates that the system is close to the threshold.

The social system topography is designed by the paradigm and the actors that adhere to and act according to it. Thus, the resilience (the topography of the system and thus the resilience variables) of the system is to a great extent determined by the actors. Resistance to change is especially relevant, I would argue, for social systems that have been designed by a paradigm. The greater the resistance to change, the more actors adhere to the paradigm. The resistance thus also captures the regime loyalty or trust. The ability to maintain regime loyalty despite system internal perturbations is key to maintain internal consistency.

Here the notion of unfortunate resilience comes into play. Assuming that a social system causes shocks in the ecosystem, which are in turn negative for the social system, it would be better if the social system transformed taking on a new paradigm. Though resistance to change (maintained loyalty to the paradigm) keeps the social system locked causing the continuation of negative impacts to the ecosystem. At some point a threshold on the ecosystem level will be reached which will potentially have major negative impacts on the social system (as it has been the case in the past as described by Chew (2001)).

Figure 13 transition process

To focus on the aspect of paradigm change Figure 13 has been developed. This Figure is a 2D version of Figure 11 only depicting one social system. This Figure is mostly meant to illustrate the process of (non-)transformation. The dot-like elements are individuals. Initially, they have the same color as the overall social system. This intends to illustrate paradigm conformity (regime loyalty). Though, due to internal and/or external disruptions, some individuals begin to distance themselves from the paradigm and move further to the edge of the system. A transition process of the individual starts through a reflection process. This slow transition process is on the one hand indicated by the increasing distance from the paradigm as well as by a change in shape and color of the dot-like element. When the individual transition has reached a certain degree the core of the dot-like element changes. This indicates an inner transformation (Woiwode, Schäpke et al. 2021) has started. As this inner transformation continues the core of the dot-like element expands until the old color has vanished and the dot-like element has completely changed its shape. The transition is completed. At this stage, the individual has adopted a different paradigm.

Though, as I have indicated before a sign of system resilience is to prevent such a paradigm shift within individuals. I suggest there might be many means how the system (these are for example individual players with vested interests, such as the WEF) can avoid a paradigm shift. One would be to not even allow individuals to distance themselves from the paradigm. I suggest this happens through the continuous provision of paradigm supporting narratives, such as the American Dream, the idea that happiness can be bought, or that the current system is the only possible one.

Once individuals start questioning the paradigm it is still possible to reintegrate them into the system. The mechanism for this is mostly the assimilation of alternative ideas within the dominant paradigm. Examples of this mechanism are the invention of weak sustainability, green growth, building back better, or the great reset. In the context of sustainability, one could subsume this under the label of greenwashing. This notion of greenwashing is indicated by the pinkish arrow within the blue social system stream.

Also, note the switch on the individual level. Instead of the core having another color, the outer layer has the alternative color. Thus, the mechanism of re-integration prevents an inner transformation, keeping the change superficial. Actors keep consuming, but now they are green consumers (pink consumers in Figure 13). Essentially what happens in case of a reintegration is that high leverage points are addressed instead of low ones. Thus, the parameters, the stocks, and flows change to some extent, but the paradigm stays the same. We are consuming now organic cotton apparel or fancy yoga pants made from plastic bottles fished out of the ocean. But we still buy way too much (more than necessary), and the products may have still been produced exploiting humans. Or we are getting an electric car, maintain our habit of using a transportation means which is essentially inefficient (because it uses way too many resources (Mobility Disruption Framework 2021). This is in contrast to shifting transportation generally or moving away from fast fashion or the need to have a collection of fancy pants. In both cases, the fancy pants and the fancy car, the green consumer may feel good consuming green, which may, in turn, increase the wish to consume more products that make one feel good. Thus, consumption itself is not discouraged. As the WEF publication, I referred to above, pointed out the goal is to enable sustainable consumer choices. Green consumption feeds into the same mechanism, into the same paradigm, as before; economic growth.

In terms of social system topography, the reintegration of actors, and thus the adaptation of parts of the social system means that the topography changes slightly. A slight change of the topography may reduce the negative impact of the social system on the ecosystem. Though, that impact may still be big enough to push the ecosystem into another equilibrium state. That push might just be delayed.

Figure 14: Transition process

Figure 14 illustrates how a social system change could be understood. First, it needs to be highlighted that within the present social system the seeds for several alternative systems exist. This is illustrated by the green and the pink dot-like elements. Which of these seeds succeed depends on the dynamics in place when the present system collapses. Here one can find another similarity with socio-technical transition theory. The niches that existed in the present system are the seed for the future. So, to some extent here too a niche takes over. However, two differentiations need to be made. First, the niche is not necessarily re-integrated into the existing system. The reintegration is a sign of resilience, which can be unfortunate resilience if the system jeopardizes the equilibrium of other systems (such as the ecosystem).

Second, the niche can also form a new system (a new and different dynamic equilibrium) when the present system has collapsed. This is related to socio-ecological thinking. This is related to the adaptive cycle in socio-ecological thinking. I cannot expand on it here. The interested reader may get the book by Gunderson and Holling (2002).To some extent, this also contributes to resilience, but now we have to think differently.

If we take a step back and look at the human population as a niche within the ecosystem itself (thanks to Christian Dorninger for looking at it this way), then the creation of a new social system based on an alternative paradigm, contributes to the resilience of the human niche. If the current system collapsed without alternatives pre-existing, humanity would end in a state of chaos.

Figure 14 depicts a less chaotic transition. Though, for sure some chaos will be there. For a transition to take place, some conditions need to be met. First, the present social system needs to collapse and make room for an alternative. To reduce the chaotic character of the formation of a new system, already preceding to the collapse, a substantial number of individuals need to have distanced themselves from the present paradigm. They need to have formed some sort of coalition before the collapse happened. When the alternative has gained enough strength and coherence when the present system collapses, the new paradigm can take over in a relatively smooth manner. This process is described by the notion of adaptive cycles Grin, Rotmans et al. (2010).

However, to understand this rather political process, I want to turn to Gramsci who may have provided a framework to understand the conditions for transition. The transition I described above, is borrowed from Gramsci’s work about the struggle of the subaltern. Explaining this will be saved for another time. The interested reader may turn to literature about Gramsci’s thoughts.

If I had to turn to development in present times, I would refer to the degrowth movement. As a sporadic observer I see that, not only is the movement gaining momentum (as also described by Vandeventer, Cattaneo et al. (2019)), but the movement is also building alliances (Löwy, Akbulut et al. 22). Thus, the movement would need to continue on this path, but they need to remain in the niche for now. They also have to be careful about their ideas not being assimilated by the current paradigm. If this happens, I would state, it will equate to the death of the movement. Just as the assimilation of the sustainability concept led to its death (meaning being watered down to suit the interest of the present paradigm). When the current system collapses the degrowth movement needs to be ready. And to think ahead any paradigm that follows will have to deal with the same peril of lock-in, stagnation, and collapse (unless potentially the rules of adaptive cycles are employed).

Presumably, the collapse of the current system will happen at some point. The reasons will be internal inconsistencies, with more and more individuals distancing themselves from the present paradigm, as well as shocks from the ecosystem (which were caused by the maladaptivity of the current social system topography).

Figure 15 subsystem coherence (a, left-hand side), subsystem incoherence (b, right-hand side)

Internal inconsistencies providing a window for opportunity is also discussed by Grin, Rotmans et al. (2010) (page 21). There the inconsistencies are referred to as fluctuations among different regime trajectories. Figure 15a, illustrates a social system with its subsystems being in perfect alignment. The subsystems have the same topography as they follow the same paradigm. A subsystem refers, for example, to the political, the cultural, the economic, etc. subsystem. They are all embedded within the social system. Indeed, these subsystems also overlap with each other, as some subsystems are part of another subsystem. For simplicity reasons, this overlap is not depicted in the figures. The small arrows between the subsystems and the system indicate constant negotiations among actors. In a sense, they show power struggles among subsystems. If all forces within the subsystems are in alignment with the system, the subsystems will have the same topography as the social system.

Figure 15b, shows a misalignment of subsystems with other subsystems as well as with the social system. Such a misalignment causes frictions and leads to individuals questioning and potentially distancing themselves from the present paradigm. Such a friction and overstepping of system boundaries within the social system would be represented by social injustices caused by the economic system. If injustice reaches a certain degree some sort of countermovement will be the result. Counter movements can be met with, for example, introducing some social standards within the economic system. However, if these standards do not solve the problem and if such problems grow, new counter movements will follow. The dissatisfaction of actors with the system will increasingly make actors question their reality, the systems they live in, and the values they follow. What alternative values actors take on cannot be predicted, but it might be related to the availability of and access to alternatives as well as the alternative's ability to provide a convincing counter narrative.

The poster:

Below you can see the poster I will present at the ERSS conference in Manchester. Maybe all the above is complete rubbish, but at least, I think, the poster looks pretty.

Steps ahead

Much has not been described in this post. For example, what are the implications for actual transition such as the energy transition? Where are the connections between socio-technical, socio-ecological and my transition concept?

I already have ideas about all of this. I have some concrete ideas about how the niche concept of my concept as well as of socio-ecological thinking better fit to an energy system that will mostly rely on renewables. The same will also apply, I believe, to the bio-economy.

I have already developed some additional illustrations, which show the connection between socio-technical transition theory, the x-curve, and the socio-ecological concept of the adaptive cycle within my concept. Thus, I am building bridges at last.

Having learned a lot about behavior science, my concept also allows to connect the mental sphere with my transition concept.

It all needs to be written down and hopefully published.

I also have to give this thing a name. I cannot continue calling it my baby and it would be weird if others referred to it as Katharina’s baby. Maybe I will keep it as it is at times done with naming living beings. For example, Pandas are only named when they got 100 days old, as this indicates greater likelihood, that they will survive infancy. Following this logic, I should not bother giving it a name and first see what its chances for survival are.

References:

Abson, D. J., J. Fischer, J. Leventon, J. Newig, T. Schomerus, U. Vilsmaier, H. von Wehrden, P. Abernethy, C. D. Ives, N. W. Jager and D. J. Lang (2017). "Leverage points for sustainability transformation." Ambio 46(1): 30-39.

Biely, K. (2022). The Behavioral Perspective. Delft, Delft University of Technology: 133.

Chew, S. C. (2001). World Ecological Degradation: Accumulation, Urbanization, and Deforestation 3000 B.C. - A.D. 2000. Walnut Creek, Lanham, New York, Oxford, Rowman & Littelfield Publishers, Inc. .

Folke, C., S. R. Carpenter, B. Walker, M. Scheffer, T. Chapin and J. Rockström (2010). "Resilience Thinking: Integrating Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability." Ecology and Society 15(4).

Forum for the Future (2020). From system shock to system change – time to transform. The Future of Sustainability

Report 2020.

Geels, F. W. and J. Schot (2007). "Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways." Research Policy 36(3): 399-417.

Göpel, M. (2016). The Great Mindshift: How a New Economic Paradigm and Sustainability Transformations go Hand in Hand. Cham, Springer.

Grin, J., J. Rotmans and J. Schot (2010). Transitions to Sustainable Development: New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change. London, UNITED KINGDOM, Taylor & Francis Group.

Gunderson, L. H. and C. S. Holling (2002). Panarchy: Understanding transformations in human and natural systems. Washington, Covelo, London, Island Press.

Im, H. B. (1991). "Hegemony and counter-hegemony in Gramsci." Asian Perspective 15(1): 123-156.

Löwy, M., B. Akbulut, S. Fernandes and G. Kallis (22). "For an Ecosocialist Degrowth." Monthly Review 73(11).

Meadows, D. (1999) "Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System." Hartland.

Mobility Disruption Framework. (2021). "The problem of automotive inefficiency." Retrieved 17.06.2022, 2022, from https://www.mobilitydisruptionframework.com/the-problem-of-automotive-inefficiency.

Naberhaus, M., C. Ashford, M. Buhr, F. Hanisch, K. Şengün and B. Tunçer (2011). Effective change strategies for the Great Transition: Five leverage points for civil society organisations, SMART CSOs.

Sovacool, B. K. and D. J. Hess (2017). "Ordering theories: Typologies and conceptual frameworks for sociotechnical change." Social Studies of Science 47(5): 703-750.

Steffen, W., J. Rockström, K. Richardson, T. M. Lenton, C. Folke, D. Liverman, C. P. Summerhayes, A. D. Barnosky, S. E. Cornell, M. Crucifix, J. F. Donges, I. Fetzer, S. J. Lade, M. Scheffer, R. Winkelmann and H. J. Schellnhuber (2018). "Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115(33): 8252-8259.

Vandeventer, J. S., C. Cattaneo and C. Zografos (2019). "A Degrowth Transition: Pathways for the Degrowth Niche to Replace the Capitalist-Growth Regime." Ecological Economics 156: 272-286.

Walker, B., C. S. Holling, S. R. Carpenter and A. Kinzig (2004). "Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems." Ecology and Society 9(2).

Williams, A., S. Kennedy, F. Philipp and G. Whiteman (2017). "Systems thinking: A review of sustainability management research." Journal of Cleaner Production 148: 866-881.

Woiwode, C., N. Schäpke, O. Bina, S. Veciana, I. Kunze, O. Parodi, P. Schweizer-Ries and C. Wamsler (2021). "Inner transformation to sustainability as a deep leverage point: fostering new avenues for change through dialogue and reflection." Sustainability Science.

World Economic Forum (2020). Markets of Tomorrow: Pathways to a New Economy.

World Economic Forum (2020). Vision Towards a Responsible Future of Consumption: Collaborative action framework for consumer industries.

Comments